In this article we dissect the definition of flavor and explain why it is different from and dependent on taste, among other important senses.

When it comes to tasting food and drink in general and craft beer in particular understanding how flavor emerges is important and can lead to enhanced and more conscious enjoyment.

What is Flavor?

Everyone knows what flavor is, right? The way something tastes or as your standard dictionary would put it – ‘the distinctive taste of a food or drink‘.

Yet defining flavor is significantly more involved. This is especially true when it comes to beer tasting.

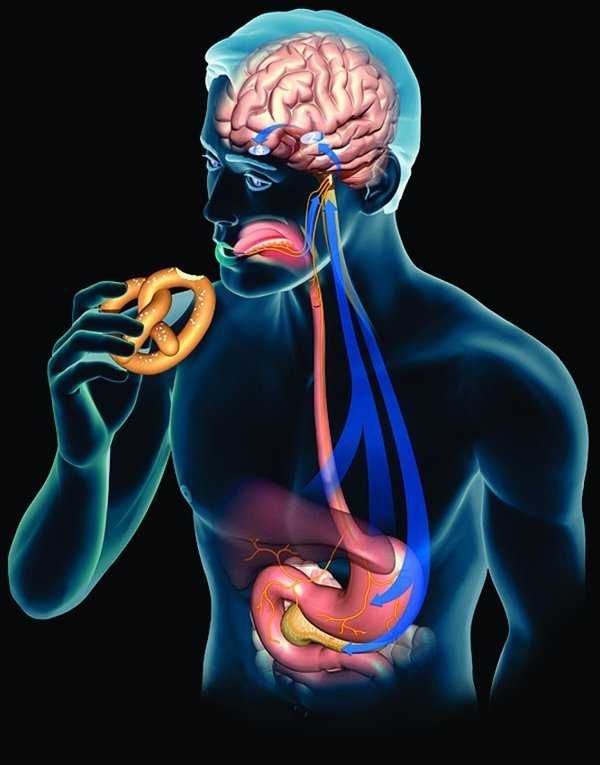

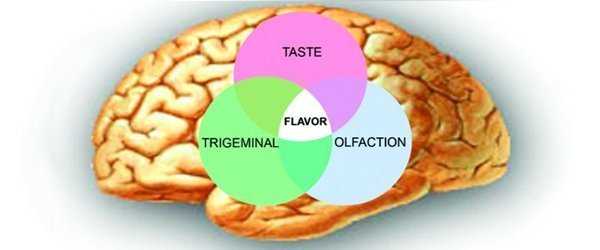

Simply stated flavor is a synthesis of complex sensory input generated by our chemical senses. The perception of flavor forms in the human brain and relies on chemosensory data generated by an array of chemical stimuli linked to taste, smell and mouthfeel. In addition, visual reception and cognition play a part.

Therefore a definition of flavor requires an understanding of the three main chemical senses – gustational (taste), olfactory (smell) and trigerminal (mouthfeel) as well as how the brain uses their input.

Taste Definition

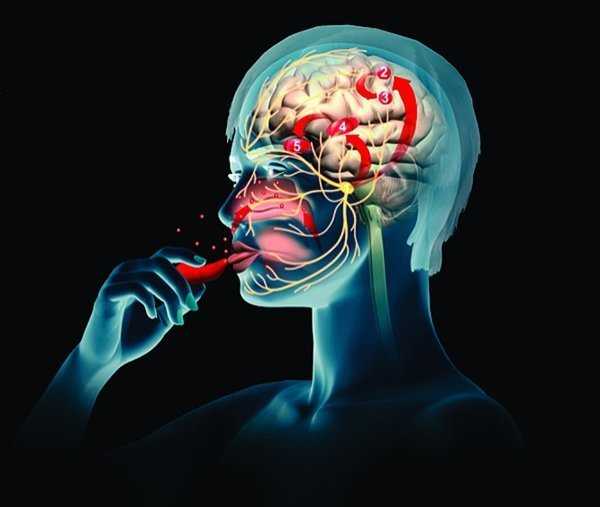

Taste is a sensory quality related to our perception of food and beverage. Our sense of taste interprets information related to the nutrient quality of what enters our mouth. Chemo receptors on the tongue’s surface receive and relay that information to the brain.

Gustation – the faculty of tasting (from gustare – Latin for to taste), is an intricate process. In addition to the taste receptors situated on the human tongue there are similar cells lining the gastrointestinal tract which also communicate with the brain.

If you are up for a short and simplified visual illustration of how gustation works – I recommend this video. If you are interested in more granular detail, this article on taste recognition is a very informative read.

Gustation is the sense of taste. Picture credit: George Retseck (Monell Chemical Senses Center) & Dr. Karen Yee (American Chemical Society)

Taste strongly influences our enjoyment of food and hence our preferences and food selection. By extension it also determines the nutrition quality and health effects of what we consume.

From an evolutionary perspective the original and most important role of taste is to ensure we get what our bodies need and stay away from what is harmful, even though considering the contemporary sugar epidemic the sensation of sweet appears to not have gotten the memo.

Salty, sweet, fat, umami fries with feta cheese (hints of sour, umami, salty) and fresh oregano paired with a bitter pilsner.

The five basic tastes are sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami (glutamate/savory deliciousness).

Among the more recently understood tastes are fat and kokumi (enhances sweet, salty, umami and also thickness/body as mouthfeel). Other tastes are about to be identified as even more specialized taste receptors on the human tongue are understood.

The perception of salty and sour is mediated via a process that is considerably shorter than that for other tastes and therefore we detect them faster than the other tastes.

Smell Definition

Our sense of smell (aka olfaction) is our ability to perceive odors and scents.

Specialized receptor cells in designated areas of the nasal cavity and the back of the mouth and throat detect smell related molecules and signal their presence to the brain.

Orthonasal olfaction and retronasal olfaction are the two elaborate processes through which we perceive aromas.

In orthonasal olfaction receptor cells detect volatile molecules coming through the nose.

Retronasal olfaction picks up on certain components of complex molecules called glycosides which are broken down by enzymes in the mouth and released to the nose through the back of the mouth.

This short video explains olfaction in a concise yet detailed manner.

Olfaction is the sense of smell. Picture credit: George Retseck (Monell Chemical Senses Center); Dr. Karen Yee (American Chemical Society)

Our sense of smell is considered the single most important factor in how we experience flavor. Aromas are more important to flavor formation than is taste.

If you’d like to test this for yourself, simply pinch your nostrils while taking a bite of a flavorful dish you normally enjoy or a sip from a well balanced and dry-hopped craft beer. You will notice a pronounced loss of flavor.

A similar experience happens when your nose is stuffy. As part of retronasal olfaction the odor molecules which usually travel from the mouth via the throat to the nose cannot be detected and food and drink suddenly taste like … nothing.

For this reason retronasal olfaction is also referred to as retronasal tasting because it combines aroma and taste. In addition, it integrates the sensation of texture/mouthfeel and weaves them in the perception of flavor.

Olfaction engages parts of the brain much larger than it is commonly assumed. Aromas detected by the receptor cells are processed by brain structures responsible for short and long term memory and involved in emotions and memory generation. For this reason smells commonly trigger emotional responses and bring back memories.

This article with detail on the importance of the olfactory sense might interest you.

Mouthfeel is a term commonly used for trigeminal sensations. Picture credit: George Retseck (Monell Chemical Senses Center); Dr. Karen Yee (American Chemical Society)

Mouthfeel Definition

The third chemical sense, mouthfeel is also known as the trigeminal sensation.

Mouthfeel includes all the sensations related to experiencing food and drink that are not smell or taste. For example the cooling sensation from mint, the signature heat and spice of chiles, the tickle of carbonation in beer.

Trigeminal sensations also include texture (such as crunchiness, density, sponginess), creaminess, richness (in beer perceived as body) and the dryness of astringency.

Pleasant, mild tannic finish is typical of Flanders style red brown sour ales.

As it pertains to flavor the astringent definition can be summed up as a pungent, dry sensation in the mouth.

The bite of astringency is often perceived well in combination with sweet or sour tastes. Astringency is the result of a contraction of mucus membranes in the mouth, caused by substances known as tannins. These are present in the bark, leaves and outer rinds of fruits and trees and make their way into our food and drink (wine, tea, beer).

In the case of craft beer the tannins come from both malt and hops, but when barrel ageing is involved the wood also contributes tannic material.

Highly carbonated Belgian quad ale poured on tap.

Carbonation, one of the signature characteristics of beer, plays a huge role in its flavor perception by way of mouthfeel. The CO2 dissolved in the liquid creates a refreshing, bright sensation and often works really well in conjunction with other mouthfeel sensations or smells.

For example German wheat beers which have a level of creaminess in result of the wheat proteins are nicely balanced by CO2. Carbonation can also boost aroma as in the case of the fruity esters in Belgian style ales.

Other Components of Flavor

Beyond taste, smell and mouthfeel there are other perceptions that shape the flavor definition.

Visual impressions – what our food or drink look like, how fresh or stale, beautifully or sloppily presented, play important roles. So do cultural inputs, age (brocolli tastes more bitter to children), sex (women can detect more smells on average) and even brand image (the packaging and marketing of a food or a beverage).

Flavor Definition

In summary – flavor itself is not a sense.

Flavor is a sensory impression created by the brain after a synthesis of the data provided by the three chemical senses – smell (olfaction), taste (gustation) and mouthfeel (trigeminal sense).

It is further shaped by how a food or a beverage is regarded – what it looks like, what one knows/feels about it, etc.

All the sensory data received during the consumption of a food or beverage allows our brain to originate the impression of flavor.

Sources

Central Processing of the Chemical Senses: An Overview by Johan N. Lundström, Sanne Boesveldt, and Jessica Albrecht

Tasting Beer: An Insider’s Guide to the World’s Greatest Beverage by Randy Mosher

Taste Perception in Humans, Neuroscience, 2nd Edition by Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors.

Taste Perception of Sweet, Sour, Salty, Bitter, and Umami and Changes Due to l-Arginine Supplementation, as a Function of Genetic Ability to Taste 6-n-Propylthiouracil by Melania Melis and Iole Tomassini Barbarossa

The Importance of the Olfactory Sense in the Human Behavior and Evolution by C Sarafoleanu, C Mella, M Georgescu, and C Perederco

Trigeminal Chemoreception, Neuroscience, 2nd Edition by Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors.

annie@ciaochowbambina says

Excellent post, thank you! It’s so interesting to think that visual impressions play a role in flavor; and that aroma is more important to flavor formation than taste is. Wow! Intriguing!